1930: The Year of the Hitters

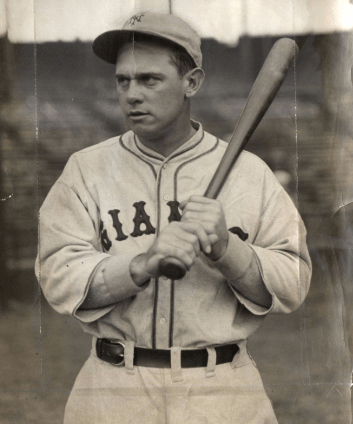

Bill Terry was the last man to bat .400 in the National League. Image credits: Baseball Fandom

Where have all the hitters gone? Halfway through the 2025 season, the composite major league batting averages were hovering around .245.

Except for the reincarnation of Babe Ruth by Aaron Judge, there is nobody to compare with the magic bats of Ted Williams, Tony Gwynn, George Brett, Wade Boggs, Rod Carew, Roberto Alomar and dozens more mid-to-late twentieth-century hitters.

It was said of Stan Musial that he could sleep all winter, roll out of bed in the spring and hit .333.

And before them there was a generation of sluggers who wreaked havoc on the record books in the 1920s, culminating in the game's most explosive season, one that will never be matched.

1930

It was the year the Jazz Age and the economy fizzled out and baseball capped a decade of change following the end of the Deadball Era in 1920, when the spitball and other pitching strategies to nick or cut or scrape the ball were banned, and new balls were put into play more often to replace the grass-stained and battered balls that had formerly stayed in play beyond their life spans.

Another factor in the game's transformation was the switch of Babe Ruth from a successful starting pitcher to an everyday outfielder and slugger. Suddenly baseball began its own Jazz Age and roaring '20s.

Playing for one run was out. Inside baseball was out. The slugging game reached its peak in 1930. There was no need for club owners to do anything to enhance the offense – no “juicing up” of the ball. There was only one rule change that added a few points to some batting averages.

Sacrifice Fly Rule

The sacrifice fly rule had been controversial for decades. It meant that a batter would not be charged with a time at bat if he hit a fly ball that scored a base runner. In some years it was called a sacrifice if it advanced any base runner after the catch.

Sometimes the rule was voted out on the grounds that the batter was really trying to get a hit and not sacrificing anything. In 1929 the rule had been voted out. In 1930 it was reinstated (then repealed again the next year). That change would have a lasting impact on one batter in particular.

Remember, we are talking about two eight-team leagues. Another thing to bear in mind is that the offensive stats for 1930 included pitchers batting. There was no DH.

The Stats

So here are the 1930 numbers:

NL teams BA: .309; AL teams BA .288. Six NL teams had team batting averages over .300, topped by the New York Giants' .319. Three AL teams topped .300, led by the Yankees' .309.

The top 10 NL batters hit at least .352, led by Bill Terry's .401 (the last NL .400 batter) and Babe Herman's .393. Terry would not have reached .400 if the sacrifice fly rule had not been reinstated. He had 19 sacrifices.

Even if a few of them were sac bunts, adding the rest to his at-bats would have had a significant impact on his .401 BA. When the sac fly scoring rule was repealed the next year, his sacrifices dropped to 2 and his batting average to .349.)

The top 10 AL batters hit at least .349, topped by Al Simmons' .387 and Lou Gehrig's .379.

The Pitchers

To what extent was the pitching of the time responsible for the unprecedented batting records? There were six 20-game winners: Lefty Grove (28), George Earnshaw (22), Wes Ferrell (25), and Ted Lyons (22) in the AL; Pat Malone (20) and Ray Kremer (20) in the NL.

The league ERAs were NL 4.97 and AL 4.65.

Today there are 30 major league teams, almost double the 16 of the twentieth century. Each of them has standing room only in the bullpen.

There's a theory that using a half dozen pitchers in a game makes it harder on hitters, but as the number of pitchers increases, the overall quality decreases. Today's league ERAs are still over 4.

The Future

Over the years, baseball has gone through other phases: war years, integration, pitchers' years, expansion years, pitching-by-committee years. Whatever the future holds, we are highly unlikely to ever see another year like 1930.