Eyewitness Account: Baseball in the 1930s

There are few advantages to growing old, beyond the simple fact of survival.

Merchants wave discounts at you, and you become eligible for social security while it’s still solvent.

Things don’t always work well in the parts department, but if memory lane is still adequately paved, when we old-timers travel down it, we realize we have something nobody under, say, 70 or so will ever experience: the thrills and excitement, the fascination and fun of growing up in the 1930s and ‘40s, when baseball was America’s domestic form of warfare and not show business.

Simpler times

When guys with names like Pepper and Ple and Piano Legs and Fats and Bobo fought it out with Slick and Hack and Peanuts and Spud.

When the average ballplayer was relatively well paid, (the average income for the country was well under $1,000 a year), but was still a working stiff who considered himself lucky to be a big-league ballplayer, and happily pumped gas or sold insurance in the wintertime to feed his family because he could play baseball the other half of the year.

When the top four teams in each eight-team league shared in the World Series pool, and that extra five hundred bucks for finishing fourth was worth scrapping for.

Multi-year contracts were rare and hungry, talented players were plentiful. Every major leaguer knew next year’s contract depended on this year’s performance, and the minor leagues were loaded with guys coveting a shot at your job.

A time for true legends of the game

Those of us who were witnesses to the decade before World War II probably saw more future Hall of Famers in action during that ten-year span than fans in any other decade that followed.

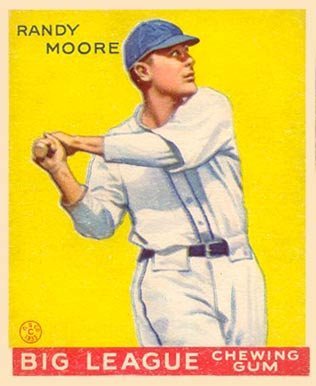

We saw the end of the careers of Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Lefty Grove, Jimmie Foxx and Bill Terry, and the start of those of Joe DiMaggio, Bob Feller, Ted Williams and Hank Greenberg – just names and faces and numbers on cards to today’s collectors, but living memories to us fortunate graybeards.

Fierce rivalries

I was triple-blessed, growing up in the New York City area, where we had the batting averages and personal tics and habits of the Giants, Yankees and Dodgers to memorize.

And if you think there’s hatred in the Middle East, you should have been a Giant fan in Brooklyn or a Dodger rooter at the Polo Grounds when those teams clashed in the traditional Memorial Day, July 4th and Labor Day doubleheaders.

Not since Athens and Sparta fought it out a few millennia ago has there been such a venomous tale of two such bitter rivals.

The Polo Grounds, New York City

One day Giants’ left fielder Joe Moore’s brother-in-law, visiting from Texas, went to a doubleheader at Ebbets Field. When he got back home he said;

“If you want to go somewhere to see some action, just go up there to see a ball game. I saw 95 fights and two games, all the same day.”

The Giants fought with the Cubs and Pirates, too, and the Gashouse Gang from St. Louis fought with everybody, especially on days when Dizzy Dean pitched.

Diz was a friend of the dry cleaners; he loved to send hitters sprawling in the dirt while giving them the horse laugh.

In those days umpires had not yet learned how to read pitchers’ minds, and the brushback pitch was not considered grounds for banishment, or a breach of etiquette like putting your elbows on the supper table.

Nobody charged the mound until somebody had low-bridged five or six in a row; then the brawls broke out.

A continuous soundtrack from the dugouts

Baseball in the 1930s was set to music.

Dugouts echoed with a raucous cacophony of ribald ridicule from bench jockeys and coaches. Nobody was immune.

It was nothing personal; nobody took more raw riding than Babe Ruth, and nobody was more beloved by other players.

Personal habits, marital problems, religion, ethnic or regional background, physical traits – all were fair game. Verbal savagery did not begin with Jackie Robinson’s arrival on the scene.

The object was to rattle the batter or pitcher to distraction or, even better, to wrath, curbing his effectiveness at the plate or on the mound. Some players ignored it; some turned themselves up a notch when under fire; some were “rabbit ears” who picked up every insult and suffered by it.

There was infield music, too: pepper, jazz, birdsong, whistles, encouraging patter.

It’s all considered bush or kid stuff by today’s corporate robots, but it kept the players a little more alert and on their toes, and it added to the distraction of the batter.

Sometimes the catcher joined the chorus; when Birdie Tebbetts was catching and Dick Bartell was at shortstop for the 1940 Tigers, it sounded like an aviary.

And in the days when ballparks were built for humans, it was audible to fans in the dollar seats and bleachers alike.

No comparison to the modern game

It’s all gone now, extinct as the ten-cent hot dog and the hundred-minute game. Most players now are businessmen concerned with image and marketing. Pepper is undignified.

The brushback pitch is impolite. Union brothers fraternize, not fight.

Most of those warriors of the ‘30s and ‘40s are gone now. Some have Alzheimer’s and cannot recall when the baseball wars were between teams and not between players and owners.

But I do, and other fortunate fogies like me do, and we salute them and thank them for the memories, and are glad that we were there.