Interview with Dave “Boo” Ferriss: Unmatched in MLB History

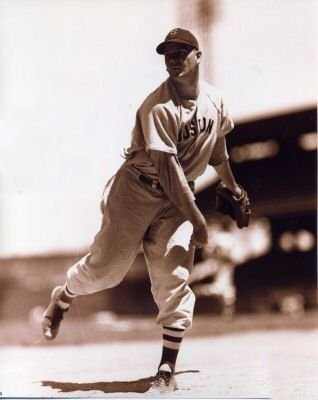

Six-foot-two, 200-pound right-handed pitcher Dave “Boo” Ferriss had one of the most spectacular debuts in baseball history, throwing a record 22 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings in his first three games for the Boston Red Sox in 1945.

His 8-0 start – beating every team in the league – earned him spreads in national magazines. In four years his record was 65-30. He never had another decision.

After five years as a pitching coach for the Red Sox, he coached baseball at Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi, for 26 years.

A few years before we visited him at his home there on January 28, 1993, the school baseball field had been named for him.- Norman L. Macht

My Father played a big part in my love for Baseball

I was born in Shaw, Mississippi, ten miles from Cleveland, population 1,500, in 1921.

The nickname Boo came from when I first began to talk and could not say ‘brother’. It came out “Boo.” The family started saying, “Boo yourself.” And it stuck. I still use it myself.

At one time Shaw was the world’s cotton center. My father was a cotton grower and buyer/broker. My mother was the postmaster for 28 years.

There were town teams with good college players all around here in the ‘20s and ‘30s, heavy rivalries, plenty of betting on games.

My dad played catch with me and took me to those games on Sunday afternoons. He was a player, manager and umpire in the Delta area, so I got my love for the game from him.

The [Southern Association] Memphis Chicks were the big team around here because our daily paper was the Memphis Commercial Appeal.

My dad took me to my first pro game at old Russwood Park in Memphis. It was a little over a hundred miles, gravel road all the way.

We usually had a couple flats along the way. Took more than three hours to get there.

As a kid, I threw a ball against the front steps for hours, drew a strike zone on those steps and imagined batters on either side of it, and I would field them when they bounced back at me or hit a corner and came back at me in the air.

My glove hung on my bike handlebars wherever I went.

We made a diamond in a lot beside my house and played choose-up games. In the seventh grade I was tall and thin and went out for the high school team as a second baseman.

My hero was the great second baseman, Charlie Gehringer. One of my first games, we were playing Shelby and I covered the base on an attempted steal and a big boy ran into me and I fell and broke my right wrist.

I was in a cast all summer, so I practiced throwing left-handed. I played second base until mid-sophomore year, when the coach put me on the mound.

Murry Dickson (right) shakes hands with Dave “Boo” Ferriss (left)

I pitched and played infield. I would pitch right-handed one day and play first base left-handed the next day and that would confuse fans.

Some guys lost money betting that that left-handed first baseman was not the same guy as the right-hander who had pitched the day before.

My high school coach, James Flack, was a hero to me. He had been a pitching prospect himself.

When the town team wanted me to pitch a big game two days after I had pitched another big game, he protected me, kept me from working too much.

The Memphis manager tried to sign me when I finished high school. Other clubs did, too. But my dad said I was going to college. I got the first full baseball scholarship given at Mississippi State.

I played semipro after my freshman year, sometimes pitching left-handed, went to the national championships in Wichita.

Attention from the Boston Red Sox

The next summer the Red Sox took an interest in me and arranged for me to play at Brattleboro, Vermont in a college league.

Then came Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The Alabama coach, Happy Campbell, was a Red Sox scout. They wanted to sign me. My dad and I talked it over.

I figured if I didn’t sign after that ’42 college season I wouldn’t be around long and might never sign.

So in the spring of ’42 I signed with Boston for $225 a month, a cash bonus of $3,000 –which I thought was a ton of money, and a $6,000 incentive bonus once I’d put in 30 days as an active player on the Red Sox.

My dad was in on the negotiations and helped me get that bonus put in there. They assigned me to Greensboro in the Piedmont League.

At three a.m. on the morning of June 7, my dad put me on a train down in Shelby to go to Greensboro. One year to the day later, he died. He never saw me pitch as a pro.

I was 20. We lived in a rooming house and ate at a boarding house. I had a 7-7 record, was not the fastest but I had a live fastball that moved in and sank on right-hand hitters. Pretty good curve. Good control. I knew how to pitch.

In the fall I went back to school and in December I was drafted, glad to have one year of pro ball behind me. I eventually finished my degree at Delta State in the winters.

Playing in the Air Force League

I was a physical instructor training Air Force cadets at Randolph Field, Texas. They had a fast eight-team league, with some major leaguers on those service teams.

It was like playing minor league ball for two years. I was lucky to have Bibb Falk, a former White Sox and Indians outfielder and legendary University of Texas coach, as our manager. He ran it like a pro club.

I probably learned more baseball from him than anybody. We talked baseball every waking hour.

I had a history of asthma growing up. In early 1945 it acted up and they gave me a medical discharge. I was on the Louisville roster so that’s where I went for spring training.

I had a couple good outings against Cincinnati.

Reds manager Bill McKechnie called the Boston manager, Joe Cronin, and told him, “You got a kid down here who’s throwing well, and you’re hard-pressed for pitching.”

We opened in Toledo and I was to pitch the second game at night. I was lying around the room that afternoon. About 2:30 there was a knock on the door.

The manager came in. “Hey, kid, pack your bag. You’re leaving at 5:30.” I was on that train to Washington, arrived on a Thursday and we went that night to Philadelphia.

I was working out and watching the games, excited to death just being there. I was riding high.

Joe Cronin had broken his leg, so a coach, Del Baker, was running the team.

It was his custom to put a new ball in the locker of the guy who was going to pitch that day. Sunday I showed up to watch another ball game.

I look up in my locker and there’s a shiny white ball staring me in the face. I took the ball and went over to Baker.

“Mr. Baker, somebody put this ball up in my locker. I know it’s not for me.”

He says, “You’re it. You’re pitching the first game.”

My stomach about fell out. I had no book on any of the hitters. We had no meeting. Baker told me, “Aw, kid, just go out there and throw strikes.”

That was about it. I didn’t know their hitters, but when I went to the mound I saw Al Simmons coaching third base. I’d read about him all my life.

He was a real jockey. And in the dugout, there sat Connie Mack. I’d read about him all my life, too. Pitching against me was Bobo Newsom, one of my boyhood idols.

The place was packed, most people I’d ever seen in my life.

How My First MLB Game Played Out

Bob Garbark was the catcher. The first eight pitches I threw were all balls. I was throwing good but just missing.

Baker comes out to steady me and Garbark tells him, “The kid’s throwing good, just missing a little bit.”

Al Simmons is really letting me have it. Bobby Estalella is the next hitter. Simmons called Estalella down the line and they talked briefly and Bobby came back to the plate ready to swing.

He swung at what was the worst pitch I’d thrown, inside. I figured he’d be taking. He popped it up foul to third base.

Next batter:. four pitches, four balls. That’s fifteen pitches, still hadn’t thrown a strike. Bases loaded.

Baker comes out again. By this time the bullpen is getting hot. Garbark tells Baker, “Del, he’s throwing good. His ball is moving. If he starts getting it in there, he’s gonna be all right.”

So Del says okay. Dick Siebert comes up. First two pitches – balls. Then finally I threw a strike. I heard it from that crowd. Oh, man, they hollered. I threw another ball. Three and one. Bases loaded.

One more ball and I might have been out of there. He took a strike and then hit a two-hopper hard up the middle over my head. I jumped for it but couldn’t reach it. I figured: base hit. I’m out of here.

The shortstop got that ball behind second base, stepped on second and threw to first for a double play. Greatest DP I ever had behind me.

I came in and they were all patting me on the back, encouraging me.

I went back out in the second inning and walked the first two men. I’d still only thrown three strikes to seven hitters. And suddenly I was throwing strikes. Pitched a shutout, 2-0.

And I was 3 for 3, singles to left, center and right off Bobo. After the second hit he took a few steps toward first and stood there staring at me.

The A’s first baseman, Dick Siebert, says to me, “Don’t pay any attention to him. He’s harmless, just got to let off steam. That’s Bobo.”

So, when I hit the third, a shot to right, he came all the way over and I mean he cussed me out for all I was worth. Boy, I was shaking in my boots. “”

That was my debut. My record for scoreless innings at the start of a career almost went down the drain in my very first inning.

What kept me from falling apart in that disastrous first few innings my first major league game, crowd ten times as many people as in my own home town?

An Even Temperament

I was always level-headed, had no temper. Errors and such never bothered me. I grew up in a churchgoing family and I always had faith and confidence in myself. I had a good stable family life.

My mother loved sports; we were a sports-minded family. I often wished my father could have seen me pitch in the major leagues.

My mother was a real rock for me, believed in me, always there to give me encouragement.

I prayed always before my games, asking the Lord to help me to do my best – not to win – just to give me the strength to do my very best.

I almost fall apart telling about it forty-seven years later.

The Boston papers gave me a big buildup after that and my next start on Sunday against the Yankees, the place was full. I shut them out, 5-0.

Then we went to Detroit where they scored a run with one out in the fifth.

I went on to win eight in a row, beat every team the first time I faced them, one team twice. That’s still a record. My first loss was in New York, 3-2.

Life magazine covered that game. It was a big buildup for those days of no television. But Boston had a zillion newspapers in the area. Every time I looked up there was a mike in front of me.

When I first got to Boston I didn’t have a locker. I had a few nails over in the corner by the bat racks. It was that way until after I had won about five, then somebody got released and a locker opened up.

But the clubhouse guy, Johnny Orlando, wouldn’t give it to me as long as I was winning.

Before my seventh game, a reporter and photographer came in with a big pair of dice made out of paper and seven dots on them.

They said, “You’re going for number seven today. If you win, this’ll be a great picture for the paper. But you may feel this is a jinx and don’t want to do it.”

So they put those dice on top of the bats where I dressed. I still have that photo; you can see my clothes hanging up on a nail.

Tom Yawkey & the Red Sox

[Red Sox owner] Tom Yawkey wanted to meet me. I went up to his office and he was there with his new wife, Jean. I came to know him and admire him, thought the world of him.

They don’t make his kind in baseball any more. He got a lot of criticism for caring too much about his players, but he said he would accept that kind of criticism.

After everybody’d left the park, he would go out and work out with the clubhouse kids and batboys. He’d swing for that green monster. Did not act like a club owner.

Bill McGowan was a good umpire but a showman. One day at Fenway I had Detroit 4-2 in the ninth with two out and two on and Hank Greenberg is up. A home run will beat me.

Count is 2 and 2. I threw one right through there. The game was over. But McGowan says, “Ball.”

Cronin put up a beef, but McGowan told our catcher, Bob Garbark, “Aw, folks come out to see big Hank hit. Give him another shot at it.”

True story. Bob said, “How about that kid out there? He’s trying to make his way.”

I was making $700 a month. I thought that was big money after being a corporal in the army. I had forgotten all about that $6,000 incentive bonus my dad had helped me negotiate.

I was just in seventh heaven being up there playing in the majors.

One day in the clubhouse amid my mail was an envelope from the front office. In it was the check for $6,000.

At the end of the season Mr. Yawkey wanted to see me. I went in and he handed me a check for $10,000. I thought that was Fort Knox.

The Boston papers had been all over him to tear up my contract and give me a raise, but he did it in his own way. In ’46 I got $15,000.

The last day of the season the team gave me a day and a used car – new cars were hard to come by during the war – a black custom-made Lincoln that had belonged to Mrs. Edsel Ford.

Had all these gadgets on it, did everything but talk. It was my first car. I drove it home and kept it a few years. It burned a lot of gas.

The Yankees beat me that day, 2-1.

I batted .267 and was never taken out for a pinch hitter that year. I pinch hit myself 20 times.

One day in Chicago I pinch hit with the winning run on second base and Jimmie Dykes, the Chicago manager, ordered me walked intentionally.

The next guy up got a hit to beat them. Well, the papers gave Jimmie the devil for walking a pitcher and getting beat by a regular hitter.

The next day, batting for myself, I hit a home run with a man on to break a 2-2 tie. As I’m going around the bases, there’s Dykes up on the dugout steps waving his cap at the press box and pointing to me.

I had a room overlooking the Charles River, near Fenway. Some of the guys I roomed with there were legends in ice hockey, but their names meant nothing to me.

All I knew about hockey is they played it on ice.

Ted Williams

In ’46 they wondered if I could win with all the big boys back from the service. In spring training the writers kept asking Ted Williams about me.

He said, “I’ve never seen him pitch. Wait’ll I hit at him.” One day I threw BP for him and afterward he told the writers, “Don’t worry about him. He’ll win any time. He’s got a good live fastball.”

I had met Williams in 1941. We had an off day at Brattleboro and Bill Barrett took me and two other kid pitchers from small towns in Oklahoma to Fenway.

We had never seen a major league game. It was the day Lefty Grove was going after his three hundredth win. He won, 7-6.

After our season was over, I and one of the other pitchers went to Boston to pitch BP, and we made one trip to New York. I saw Lefty Gomez pitch against us.

The harder he threw, the harder Ted hit them, three shots. That was Ted’s .406 year.

Now I was enthralled to be his teammate. First thing that stood out to me was how hard he worked.

Likable guy, always popular among his teammates. Knowledgeable about hitting and never stopped helping anybody who would listen.

It was just a few Boston writers who gave him a bad time. But he did not work as hard on his fielding.

You’d look out there from the mound before you started pitching and he’d be standing there taking those imaginary swings.

We got off to a great start, 41 and 9. But I got off to a bad start, knocked out in my first two games, and right away they started writing, “He’s done. The big boys are back.”

I knew the level of player would be higher. A player who helped boost my confidence the most was Bobby Doerr, a fine fellow and our unofficial captain.

One night in St. Louis rain held up the start of the game. Water everywhere. But they had a big crowd. Our warmup mound by the dugout was in a big puddle of water so I couldn’t warm up.

Over on the third base side the Browns’ pitcher could warm up okay. Cronin told umpire Cal Hubbard about it, and he said I could warm up on the mound.

So the last half of the first inning, I go out and start warming up. Here comes St. Louis manager Luke Sewell. He kept kicking about all the time I was being given and protested the game.

Our guys were agitated about playing on a wet field and said, “Aw, let’s beat the stew out of them.” Well, they beat us, 1-0.

[The Red Sox won the pennant by 12 games.]

On the last day of the season we packed our bags and took them to the ballpark not knowing if we were going to Brooklyn or St. Louis for the World Series.

The National League ended in a tie and we kind of went flat. We had to go back home and unpack and wait for their playoff.

Cronin brought some American Leaguers to Boston to play us to keep sharp. But that delay took the edge off us.

In one of those games, Ted Williams was hit on the elbow with a pitch. Ted was 5 for 20 in the World Series against the Cardinals, all singles.

We felt he was not himself. He was in the whirlpool every day. We didn’t think he was swinging his normal swing.

I started Game 3 and had a few more butterflies than usual. Dizzy Dean was out on the field. He was a broadcaster for the Browns then.

He was around the batting cage, wearing a big ten-gallon hat and cutting up as usual.

After I took my BP swings. he threw an arm around my shoulders and told me, “Kid, just go out and throw the way you been throwing all season. After your first pitch, it’s just another game.”

He was right. [Ferriss won, 4-0.]

The night before Game 7, my brother and I went to the picture show. He was crossing his legs the whole time, nervous as he could be.

I said to him, “Who’s pitching tomorrow, you or me?”

That was a real thrill, pitching that seventh game. That’s what kids dream about when they’re throwing a ball up against those steps, making up an imaginary setting and game.

They weren’t hitting me hard, but I came out trailing 3-1 in the fifth. Dom DiMaggio tied it in the eighth with a double, but pulled a hamstring going into second base and had to come out.

Culberson replaced him in center field. Bottom of the eighth, I was in the dugout [when Enos Slaughter singled],, but I was out on the steps soon as Harry Walker got a hit and Slaughter took off from first.

It was a 3-1 pitch and he was running on the pitch, a run and hit situation. He was past second when the ball hit the ground. We never dreamed he was going to try to go all the way.

The third base coach tried to hold him up, but Slaughter had his head down.

Pesky hesitated a second after he took the throw in from Culberson, but he had to. When they saw Slaughter going, Doerr and Higgins are hollering, “Throw it home.”

But Pesky couldn’t hear them. He had to hesitate long enough to see where to throw it and he made a good throw, but it short-hopped and the catcher had to come out in front of the plate to get it.

A throw on a line would have wiped Slaughter out. Pesky got the goat horns, but he did not hold it any longer than he had to and his throw was hurried.

We had men on first and third with one out in the ninth but didn’t score.

In a night game in Cleveland in July of ’47 I threw a curve on a 3-2 count with two out and the bases loaded in the seventh inning of a 0-0 game -- got on top of it and cracked down on it and struck him out.

Doerr won it, 1-0, with a home run in the ninth.

Didn’t think anything about it at the time. Next day in Chicago I went out to loosen up and couldn’t get my arm up. That was the start of my arm trouble.

I laid off for two weeks but did not have my good stuff. Finished 12-11.

That winter they worked on it, but x-rays showed nothing. Joe McCarthy had replaced Cronin as our manager. Our relationship with Cronin had been personal. McCarthy held a distance.

We all liked Cronin and had to adjust. I was a spot starter and reliever. On the last day of the ’48 season we had to win and Detroit had to beat Cleveland for us to finish in a tie with the Indians.

We were watching the scoreboard and Cleveland was losing.

I worked the last 3 2/3 innings against the Yankees and we won, 10-5. We finished in a tie.

We all went to Fenway thinking Mel Parnell was going to pitch the playoff game.

After the Sunday game we said to him, “We’ll get ‘em tomorrow.” We were all surprised that it was Denny Galehouse who started. The Indians were hot. [Cleveland won, 8-3.] That was a sad day.

Spring training 1949 my arm went dead. My good fastball was gone. I stayed with the team all year on the disabled list. The next year they sent me to Birmingham.

Pinky Higgins was the manager. I did pretty well for him, pinch hit a lot, but my good fastball was gone.

Then he went to Louisville and I went with him as his pitching coach. When he went to Boston in ’55, I went with him.

I can still remember how I pitched to certain big hitters. I can visualize a curveball I threw in the ’46 World Series to strike out Enos Slaughter – still see the path of that curve breaking right in there.

It fooled him, and you didn’t fool him too much. I had pretty good luck against the Yankees.

I side-armed Joe DiMaggio after I got ahead of him and kept it away from him. Curve on the outside. Tommy Henrich and Charlie Keller were lefties.

They were tough. I remember this pitch: I had Henrich 3 and 2 in New York. I threw him a changeup. He was not looking for that from me on that count.

He got way out in front of it and the ball sailed out over the third baseman’s head. He just clapped his hands and laughed all the way to first base, saying, “You can’t do that.”

My choice of a defensive infield behind me would be Joe Kuhel first base, Doerr at second, Phil Rizzuto shortstop, and Ken Keltner third base.

When Keltner had time, he always looked at the ball and got his fingers across the seams before he threw.

Seems he made a bad throw once as a teenager and his daddy beat him with a stick and he never made another bad one.

Leaving the Red Sox and Fenway and coming to Delta State, where there was practically no baseball program, no field, not much of anything – it hurt. It took some adjusting.

I had an offer to be the Twins’ pitching coach. I almost went, but I stayed here and am glad I did.

College baseball as a whole has been upgraded. Been to the Division II World Series three times. Had a lot of good kids.