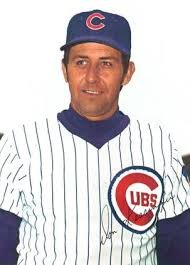

Don Kessinger: Baseball’s Last Playing Manager

Picture credits: Custom Throwback Jerseys

Don Kessinger was the shortstop on one of the Chicago Cubs’ greatest – and most ignominious – teams, the 1969 club that led the Mets by 9 games on August 15 and finished 8 games back in second place.

A six-time All-Star, he spent twelve of his sixteen years (1964-1979) with the Cubs, the rest with the Cardinals and White Sox, where he was baseball’s last playing manager in 1979.

He played in the College World Series for the University of Mississippi, where he later coached for six years before becoming Associate Athletic Director.

He seemed to be the most popular person in Ole Miss’s hometown of Oxford when we visited him in his office in August 1997; wherever we mentioned our reason for being in town, people responded with, “He’s the nicest person; say hello to him for me.”

This is his story.

I had several offers when I graduated in 1964 and chose the Cubs. Some other teams offered more money, but I felt they offered the best opportunity to get to the big leagues. I was right; I spent half the ’64 season and the first two months in ’65 at Ft. Worth and that’s all in the minors.

Playing For Leo Durocher

Leo Durocher became the Cubs’ manager in 1966. We all knew about his past, his reputation. He didn’t believe in private meetings. If he had something to say, he said it to the radio, TV, newspapers. Open clubhouse meetings. That’s the one negative thing I’d say about him. One day in spring training reporters came to me and said, “Leo says he has to find a shortstop. Kessinger can’t hit, field, or throw.”

Did he say that to challenge me? I don’t think so. Leo just said what he thought. I’m just a young kid. Leo runs the show. If I say the wrong thing in response, I could be gone. I said, “Well, I’m glad he thinks I can run.”

There was a challenge there, but it didn’t make me change what I did. I was very happy that it turned out he was wrong.

We had finished eighth in the ten-team league the year before. Leo announced, “I guarantee you this is no eighth-place ball club.”

He was right; we finished tenth. Had an awful team. I give Leo credit. He had the courage to play a lot of us young guys, making lots of mistakes. Leo was in charge. There was never any doubt that he was making all the decisions. I learned a lot of baseball from him.

When he went out to the mound, he’d ask the catcher, “Has he lost it?” He’d expect the truth. You don’t always get that from the pitcher. He was always an inning ahead, knew what he wanted to do next. Maybe he was harder on me because he had been a shortstop. If he was on you, he was trying to make you better. If he ignored you, you were in trouble. I don’t believe his demeanor was always the way his reputation said it was.

People think playing for him was so difficult -- strict, on you all the time, and it was the opposite. He liked to put the same lineup down every day and let you play. He wasn’t concerned with curfews or what you did off the field, wasn’t a driver that pushed you during BP. None of that.

He was a fierce competitor, hated to lose, and during a game he could get upset, get on you, but that’s okay. When people think of him as being tough, hardnosed, it’s a little bit misdirected. He was not hard to play for in that sense.

Our personalities were worlds apart. It took some time for Leo to understand that the game was really important to me. I played hard, gave it all I had, even though I didn’t have the volatile temperament he had.

What made him hard to play for was that he was very open and vocal with his criticisms and that’s somewhat difficult to handle. But that was the only aspect of Leo Durocher that I found tough.

The next year we went from tenth to third. We had more experience, traded for Ferguson Jenkins and Randy Hundley, brought up Joe Niekro. From then on we were always contenders, with Ernie Banks, Billy Williams, Glenn Beckert, Ron Santo.

Playing at Wrigley Field

Do I think we should have won some pennants during Leo’s years in Chicago? Absolutely. We had the best talent in baseball and we didn’t win. I don’t know why. If we had won in ’69, we probably would have won the next two or three years. But there was a stigma attached to not winning that year.

There are a lot of different reasons for that. Did we get tired? Maybe. Playing all day games in Wrigley I think contributed. It was a particularly hot summer in Chicago. I always lost about ten pounds playing with the Cubs and at that time I couldn’t afford it. I think it was a contributing factor.

Later, when I went to the Cardinals, it was hot in St. Louis but we played at night and by September I hadn’t lost any weight and still felt strong. The same thing when I came back to Chicago with the White Sox. I was older but still felt strong in September.

No, we did not play well down the stretch [9-18 in September] but people forget that the Mets won at a phenomenal pace [38-11 from mid-August]. Hot is not the word for it. That may never happen again. Nobody is that great. If they had played normally, we’d have won.

Career Highlights

My personal highlights: The 1969 All-Star Game when four of us Cubs – Banks, Beckert, Santo and I – were the NL infield. I think Ron Santo belongs in the Hall of Fame. I played alongside him for a number of years and I didn’t realize until he wasn’t there how much ground he covered at third base.

Suddenly, I’m trying to throw guys out on balls I never had had to get to. If we’d played in two or three World Series, he’d be in today. I think one day he will. [Santo was elected in 2012.]

My 6-for-6 game in June 1971, I was tired. When I left home that morning, I told my wife, “I need a day off.” Steve Carlton was pitching for the Cardinals, and I was like 0 for three years against him. She said, “Why don’t you tell Leo?” I said, “Yeah, sure.” My first four hits were off Steve. The sixth hit led off the tenth and I scored the winning run. It was that kind of day.

For a shortstop, the toughest play is a ball hit straight at you. No question about it. You have no angle on the ball. You can’t tell how hard it’s hit. Playing at Wrigley, for about four innings you were fighting that sun on popups. That was tough. As a shortstop, if you’re really in the game, you’re out there thinking like a manager – what’s the other team going to do?

Managing

I’d been with the White Sox since 1977 when Bill Veeck asked me to manage the club in 1979. We were a fifth-place club in the seven-team division. I enjoyed it, but I did not feel that under the circumstances the White Sox were going to be a contender.

Veeck didn’t have the money for the free agent market and that’s where you had to be. I thought it was not going to get any better.

I’d learned some things about managing. One thing was that if you have rules, you have to enforce them for everybody. So you don’t want to have too many rules. One manager I had handed out three pages of rules.

I learned the three most important musts for a manager:

1. Know when to take a pitcher out.

2. Never ask a player to do something he can’t do. No matter what you think the fans or the GM or the writers think you should do. If the situation calls for a bunt and you know the guy at the plate can’t bunt, don’t ask him.

Let him swing away or put in somebody who can. If you ask him to bunt, you’re doing it to protect yourself. You’re not giving your team the best chance to win, just giving yourself an excuse for failure.

3. Try to keep the guys who are not playing every day sharp. You can’t keep them happy. Play them enough to keep them sharp. Calling on a guy to pinch hit in the eighth inning, bases loaded, score tied, he becomes the most important guy that’s going to play in that game that day. And if he hasn’t been to the plate in three weeks, you’re asking an impossible thing of him.

Don Kessinger played for the Cubs, Cardinals and White Sox - where he was the last playing manager. Picture credits: Wikipedia

The toughest thing in baseball is to be a defensive replacement. You can only fail. If you make the play, you’re expected to. If you miss it, you’re the guy that fouled up. Managers have to realize those things.

We had a poor defensive club. You can’t teach instinct. My coaches kept telling me, “You need to play.” I should have listened to them more. I didn’t want the players to think I was playing myself because I was the manager.

Another thing made it difficult for us. My weakest part of managing was handling pitchers. I had hired Fred Martin, an experienced coach in the Cubs organization, to be my pitching coach. We found out on opening day that Fred had cancer. He died in June. Veeck paid his salary for the rest of the year, but had no money to replace him. So we deactivated one of our pitchers and made him the pitching coach.

People think that when a manager resigns, it’s because he was asked to, but that wasn’t so with me. I’d been thinking about my future, and in August we are not going anywhere. I decided to not come back the next year.

On an off day I told Bill Veeck, “I love you, but I’m not coming back next year. I’m telling you now so you can handle it however you want to.” He said, “I want you to come back. You’re not being fired. But if you’ve made up your mind, I will go ahead and bring in Tony LaRussa.”

LaRussa wanted to be a big league manager. He had been given a choice of coaching in the majors or managing in AAA, and I had advised him to go down and manage.

Today’s athletes are bigger, stronger, faster and better than we ever were. Ballplayers are better than we were. The guy who has the mental toughness will succeed.