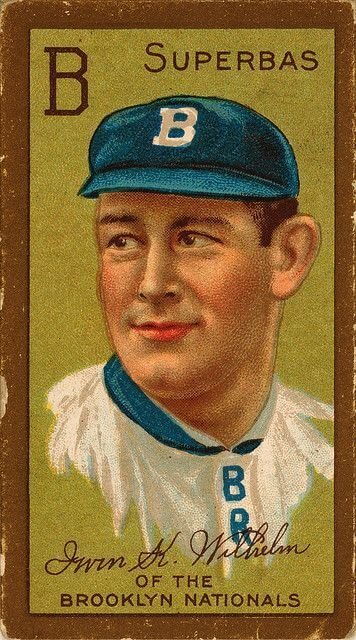

Irvin Wilhelm: The Phillies Manager Who Hated His Nickname

‘The Kaiser’

More than any other athletes, baseball players used to attract colorful nicknames. You never heard of NFL mastodons called Bucky or Babe.

Even the tag “Lefty” never attached itself to southpaw quarterbacks.

Nobody called the storks in the NBA “Slim” or “Highpockets,” the way a seven-foot first baseman would have been labelled.

Please don’t call me Kaiser

Irvin Key Wilhelm, of Wooster, Ohio, was a pitcher in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

So, when the real Kaiser Wilhelm II rattled his German sword and shook the world into World War I, there was no way Irv could avoid being stapled with the same moniker.

No matter how much he protested, the label stuck to him even until his obits in 1936.

Irv “Please Don’t Call Me Kaiser” Wilhelm started at the top in the major leagues and worked his way down in a hurry.

An unwanted record

A rookie at 29 with the 1903 Pittsburgh Pirates, the six-foot right-hander won 5 and lost 4 for the National League reps in the first official World Series.

From then on, every big league team he pitched for or managed lost at least 90 games and finished no higher than sixth, except for an ascent to third with the Baltimore Terrapins of the Federal League.

On the way to a 56-105 lifetime record, he set an NL standard for futility in 1905 that has seldom been approached, winning just 3 of 27 starts, with 23 losses.

He suffered through some long afternoons, going the distance in 20 of his losses. Mingled among his seven years in the majors was a lot of minor league mileage.

Moving on to coaching with the Phillies

In 1921 Wilhelm was “promoted” from Jersey City to be a coach with the perennial cellar-dwelling Phillies.

Although the war had ended two years earlier, Philadelphia writers ignored his pleas to drop the nickname and immediately dubbed him “Kize” Wilhelm.

Club owner William F. Baker believed that the most profitable way to run a ball club was to pay nothing in salaries, sell anybody who showed promise, and fire managers for failing to win without major league talent.

The joke around the leagues was that Baker’s payroll was only $250 a month, and star center fielder Cy Williams got $200 of it.

‘The Kaiser’ moves into management

When the axe fell on the manager, Wild Bill Donovan, on July 25, Kize replaced him.

“I do not think Bill Donovan is disciplinarian enough for a baseball manager,” said Baker, adding – with a straight face, “Our success is too important to keep an inefficient man in charge.”

Wilhelm inherited a team that was banged up, hung over, or – in the case of the pitchers – unwilling to pitch, especially at home, with a porous infield and a short – really short (280 feet), tin fence in right field looking over their shoulders.

He tried fines to improve the players’ conduct, even kicking one off the team until he sobered up, a practice which, if carried to its extreme, might have endangered the manager’s ability to field nine men.

Expected to be no more than an interim manager, Kize was signed in September for the 1922 season, perhaps because, as The Sporting News correspondent James C. Isaminger wrote, “It is difficult to believe that any baseball man of reputation would come here under present conditions.”

Wilhelm was hailed as something of a miracle worker when he lifted the Phils to seventh in ’22 with a 57-96 record.

He produced a hustling, fighting team that actually tried every day, to the delight of the fans if not the owner.

With a league-leading 116 home runs, the team was called “Kize Wilhelm’s Home Run Congress,” but the pitchers’ ERA also was the highest.

The team’s spirit and its season were summed up on August 25 in Chicago.

The Cubs led, 25-6, after four innings, but the Phillies fought back, scoring eight in the eighth and six in the ninth before succumbing, 26-23, in the highest-scoring game in the books.

“No manager could have done better with the collections of rots and spots that represented the Phils this year,” wrote Isaminger.

As a reward, Kize was fired. Wilhelm dropped quickly from the big league scene. He did some scouting and minor league managing.

Given another chance, he might have been a successful manager.

Instead, he is remembered mainly for a trick of European genealogy and history that stuck him with a nickname he didn’t like and couldn’t escape.

Even Rube or Dazzy or Boom-Boom would have been easier to take.