“The Vulture”: An Interview with Phil Regan

Phil Regan began his 13-year big league career as a starter for Detroit (1960-1965), and became a dominant closer with the Dodgers and Cubs before closing his career with the 1972 White Sox.

Sandy Koufax nicknamed him “The Vulture” because of his knack for earning wins in late-inning relief (14-1 in 1966).

Stints as a pitching coach with Seattle and the Cubs surrounded his lone year as a manager – at Baltimore in 1995.

One day in June in the tiny manager’s office at Oriole Park, he surprised us when he said that, despite having played for pennant-winning managers Leo Durocher and Walter Alston, the one he learned the most from was a guy who finished ninth with the Cubs in his only big league season. – Norman L. Macht

Phil Regan on the Mental Side of Baseball

I really learned a lot from Charlie Metro with the Denver Bears in 1960. He believed in positive thinking, and he gave us the mental outlook that we were good ballplayers.

One day I said to him, “Charlie, some days as a pitcher you go out there and you don’t have good stuff.”

He said, “Geez, don’t ever say that. You always go out there with good stuff. Some days it’s better than others, but you never go out to the mound when you don’t have good stuff.”

Now I tell my pitchers, “Anybody can go out and win when they have good stuff. It’s when you don’t have it that you have to pitch.”

One night I was pitching against St. Paul and it was 1-1 in the eighth inning. First batter bloops one down the left field line for a double and the next guy bloops into right field and they go ahead, 2-1.

Metro comes out to the mound and says, “Gimme the ball. You’re giving up.”

I said, “What are you talking about?”

He said, “That guy’s holding us, and you’ve got to hold them until we can get a run. I’m bringing in a relief pitcher.”

Later he told me his point was that just because you’ve pitched a good game until the eighth inning doesn’t mean you’re going to win. You’ve got to continue to bear down and hold them.

Another theory of his was, “If I bring you into a ball game and a batter hits a line drive 400 feet and a guy catches it, I don’t care. You did the job.

But if I bring you in and he hits the ball in the hole or bloops one for a hit, you didn’t do the job.

The bottom line is to do the job no matter what it takes. You can’t tell yourself you made a good pitch and the guy blooped it. That doesn’t do the job.”

Maybe that doesn’t sound fair, but it’s a mental approach. No excuses, because pretty soon, if you continue to think that way, you’ll always have an excuse for why you lost.

Regan on Coaching and Management

As a pitching coach, I had a pitcher who never had a winning year, from the minor leagues to the majors, and he was making almost a million dollars.

I had read in the papers that he was a hard-luck pitcher. He loses 4-3, 3-2, 2-1. So one day I said to him, “Do you think you’re a hard luck pitcher?”

He said, “Yeah.”

I said, “That’s why you are because you think you are.” And that’s true. If you come to a point in a ball game where you think you’re going to lose, then you’ll pitch to lose instead of pitch to win.

Metro couldn’t manage in the majors. He had very strict rules: no eating and no shaving in the clubhouse. But he sent a lot of guys to the big leagues who believed that they were good ballplayers.

Not all the advice you get is helpful.

I was with Detroit and the manager, Charlie Dressen, told me, “If you could throw a curveball like Sandy Koufax and a changeup like Johnny Podres, you’re going to win.”

I said, “No kidding.”

[Regan played for two managers who were totally different, Leo Durocher with the Cubs and Walter Alston with the Dodgers.]

Leo Durocher

Leo was loud, and brash. You could never outtalk him.

One guy said Durocher could be in a room full of atomic scientists, know nothing about the atomic bomb, and in thirty minutes he’d tell them how to build it.

He never changed in thirty-five years of managing. When we were winning, he was really sharp, ahead of the game, on top of everything, getting on the players.

One day we won a game, playing well. But in the game, Ron Santo went from first to third on a play and it was a close play at third.

I don’t remember if he was safe or out. But as soon as we came off the field, Leo closed the clubhouse door and pointed at Santo and said, “That’ll cost you $200 for loping into third and not running.”

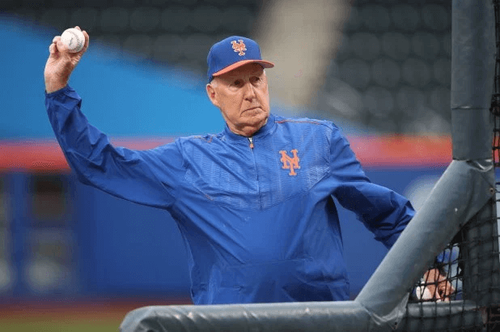

Baseball legend Phil Regan

But when we were losing, he was the opposite, very quiet, didn’t get on the players at all. It’s almost like he lost interest in a club that didn’t contend.

But I enjoyed playing for him because coming to the ballpark every day was exciting. You never knew what he was going to do or what would happen.

He was tough but he was a good person, a side of him that was not reported or written about.

We had a clubhouse meeting in Chicago and there was almost a players’ revolt against Leo and he took off his uniform and was going to quit.

My roommate, Jim Hickman, a quiet guy from Tennessee, was the one guy who stood up for him.

He said, “You guys can’t do this. You’ll be known in baseball as a bunch of quitters,” and he went on, and Leo came back.

Years later Hickman had some financial problems and Leo called him and said, “Hick, I don’t have a lot of money, but I’ve got $235,000. If it’ll help you, you got it.”

That was the kind of guy he was. He backed his players to the limit. If you hustled for him and were loyal to him, he was intensely loyal to you.

Walter Alston

I really enjoyed playing for Walter Alston and the Dodgers. He was very quiet, but tough when he had to be. He never questioned you about an error you made or a bad pitch.

But he couldn’t tolerate mental errors, like not covering first base or backing up a base.

Soon after I joined the club we were in Houston and the night before, Don Drysdale – big star, Cy Young winner, making $100,000, big money in those days – had failed to cover first base on a ball hit to the right side and the guy was safe.

The next day Alston called a meeting and just chewed out Drysdale, who sat there and took it.

Alston ended by saying, “I’ll tell you one thing, if that had been Don Sutton” -- a rookie that year -- “he’d be on his way to Spokane today.”

Drysdale understood him, Alston was making his point to the rest of the club early in the year, that he wouldn’t tolerate that.

Once, coming out of Pittsburgh after we’d lost a game, some of the guys were complaining about the air conditioning on the bus.

Alston stopped the bus and invited anybody who wanted to complain to get off the bus and he’d handle it right there.

But he was more of a teacher. He’d have classes in spring training and diagram plays, how he wanted them executed. He’d hold classes on the rules of the game.

No one else that I ever played for did that.

Alston won with all different types of clubs. He adapted to what he had – hitting, speed, pitching, young players. You have to manage with what you’re given and he did that.

When I got this job managing the Orioles, I got a letter from [Dodgers executive] Buzzie Bavasi: “Don’t try to be Leo Durocher. Don’t try to be Walt Alston. Be Phil Regan.”

[Regan was fired after finishing third in the AL East, a victim of the truth of an axiom from longtime Orioles pitcher Mike Flanagan: “It’s not the best pitching staff that wins; it’s the healthiest.”]