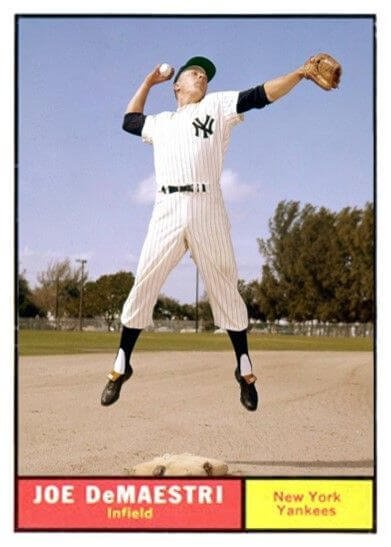

Joe DeMaestri: From Rags to Riches

After a fourth-place finish in his rookie year with the Chicago White Sox (1951), shortstop Joe DeMaestri dwelt deep in the second division for seven years with the St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia/Kansas City A’s.

He was ready to quit the game when he was traded to the Yankees and wound up in the 1960 and ‘61 World Series. For most ballplayers, their most unforgettable moment was a career highlight.

For DeMaestri, it was an inglorious lowlight, as described by him at his home in Novato, California, in August 1995 – Norman L. Macht

Starting out in the Minors

After five years in the minor leagues, I was drafted by the Chicago White Sox and went to spring training in 1951 in Pasadena. Paul Richards was the manager.

Nellie Fox was on the verge of being shipped out. He fielded every ground ball down on one knee, and he wasn’t hitting. In his stance, his feet were pointing in different directions.

At that time, you couldn’t see what he would turn out to be. Doc Cramer was a coach. Cramer said, “We’re going to teach Nellie to hit.” He sent me to the outfield to field the hits and gave Nellie a bottle bat.

He started hitting and using that bottle bat after that.

Paul Richards was the toughest and best manager I played for. He was two or three days ahead of everybody in his thinking. But he never got close to his players. He was a loner. Never smiled. Never a pat on the back.

You could not corner him to talk to him. In his office, yes, but don’t try to strike up a conversation with him because it wasn’t gonna go. I learned how to keep my eyes open and mouth shut.

Coming off the bench

Staying in shape while riding the bench and never knowing when you might get in a game is the toughest thing in baseball.

It’s the middle of June and we’re in first place. I hadn’t started but once, had made one hit. We’re at Fenway Park and Mel Parnell is pitching for the Red Sox.

We’re a few runs behind in the fifth inning and our pitcher is due to lead off. Richards looks down the bench and says, “DeMaestri, get a bat.”

I’m telling you, I felt like I was walking on eggs. Your whole life changes. I’m what – twenty-two years old. I get a bat and Parnell threw me a couple pitches. I swung and I knew I hit the ball.

I swear to God, to this day I could never remember where it went when I hit it. But I knew I hit it good. I take off and I’m running, and I don’t pay any attention to the coach. I’m running for a double.

The ball hits the top of the fence in left field and Ted Williams could play that left-field wall like he was in a rocking chair, but I don’t know that.

He just waited for the ball to come back to him and turned and fired it into Bobby Doerr at second.

I get about a third of the way to second and all of a sudden, my legs don’t want to run anymore. I’m starting to go down. Doerr gets the ball, turns around to make the tag and I’m not there.

I ended up flat on my face about from here to that fireplace from second base. I just couldn’t move. Doerr sees me and walks over and says, “Are you hurt?” I said, “No.” He says, “Well, you’re out.”

Now I gotta get up and go back in that dugout. Richards is sitting at one end of the bench with nobody near him.

They had a restroom at the other end of the dugout; you went through a swinging door and down a short hallway to get to it.

There were twenty-four guys pushing and shoving to get in that doorway, they were laughing so hard and they didn’t want Richards to see them.

I went into the dugout and sat down. Richards didn’t look at me. Never said a word. His face was like stone. That was typical of him.

I knew what was going through his mind. It would have made me feel better if he’d chewed me out. I learned a lesson – watch your coaches. The first base coach knew how Williams played that wall. He’d have held me up.

My wife had flown back to Chicago; she was pregnant with our first child. When I get home, she’s waiting for me with this newspaper photo of me flat on my face in Fenway Park.

A few years ago our first baseman, Eddie Robinson, came through here scouting and we met for dinner and we had just said hello to each other and Eddie says, “I’ll never forget that night in Boston. . .” That’s after forty years.

Signing for the Red Sox

I was originally signed by a Red Sox scout, Charlie Wallgren, a friend of my dad’s.

I had some high school teammates who got $10,000 bonuses, but I was ready to sign for nothing, I wanted to play so bad. My mother finally wrung a $600 bonus out of them.

I signed for $140 a month, bounced around in Class C, lived at the YMCA, and rode a red school bus on the road. I was up to $225 a month in Birmingham when the White Sox drafted me.

Playing with the Browns

After that ’51 season, they traded me to the Browns. That was a horror story. Rogers Hornsby was the manager, a rough guy for a young player to get involved with.

We played an exhibition game in San Francisco and he wouldn’t let me go home across the bridge.

He said the only two people he’d pay to see were Jim Rivera and Clint Courtney. Rivera was a wild man, and Clint was a tough, tough guy, who got in fights all the time, and could not throw the ball back to the pitcher.

With a man on first, I’d stand between the pitcher and second base in case he threw it over the pitcher’s head.

Hornsby hated Satchel Paige. But Satch could handle him, cause he had the owner, Bill Veeck, behind him.

In spring training we were sitting in the bleachers and Hornsby was going over the day’s schedule.

No Satch.

He’s talking to us and here comes Satch, sneaking in behind him. Hornsby got on him. “I’m fining you $250 for this” and on and on and Satch just stood there and said, “I don’t think so.”

It got to where there were guys who were going to refuse to play for him. We were in Boston and we all got together. I don’t think there was one leader, maybe Marty Marion and Bob Young, who were roommates, were seen as leaders.

Veeck came to Boston and fired Hornsby, We all chipped in and gave Veeck a huge trophy.

Getting traded to Philly

That winter I was traded to the Philadelphia A’s. The A’s didn’t have any more money than Bill Veeck.

One night after a series at home against the Yankees, both teams were at the train station and I saw how the other half lived. They had dining cars on their train and we had box lunches.

I’d been making the minimum $5,000 for three years. In ’54 I held out for $6,000. After a lot of back and forth, I finally got it.

We were there for two years. Didn’t have a car, so we rented a row house two blocks from Shibe Park. Italian neighborhood.

I’d come home after a night game and the guy next door would be sitting on his porch waiting for me. Had to sit and drink wine with him before I could get home.

But the neighborhood was changing. Some people were trying to incite race riots in the area. That last year was a tough year.

That fall, I heard on the radio that the A’s were going to Kansas City. That was the first I knew of it. We enjoyed our five years in Kansas City. Didn’t win, but it was a nice place for the family to spend the summer after Philadelphia.

After the ’59 season, I was ready to quit. I had a young family and my dad and I had a Budweiser distributorship.

I’d had nine years in the major leagues and things didn’t look any rosier at that time, so I figured that was enough.

Getting a call from the Yankees

Then I got a call from the Yankees: they’d made a trade for Roger Maris and me. In those days it was pretty definite you’d be in the money with New York. Best move I ever made.

The GM, Roy Hamey, asked me how much I wanted. I said, “Twenty-three thousand.” He said, “Get out of here.” I left and was going to quit. But I got it. I was surprised at how little the players were making in New York.

My first spring training with the Yankees, I was sitting in my locker and all of a sudden there were about five guys around me – Skowron, Berra, McDougald. They had lost to the White Sox in ’59 and they weren’t used to losing.

We were talking and they said, “Just remember, every time you take the field, you’re playing with our money.” That never left my mind.

Roger Maris was a friendly guy, a team guy who went out with us. He was wary of strangers. He didn’t know how to handle the press, but in Kansas City he never had to. We had only two or three writers and got to know them well.

In New York, there were a lot of young inexperienced guys from small area newspapers. If somebody asked Roger a dumb question, he’d fire back at them.

In 1961 it hit him overnight. I can still see Mantle sitting there laughing while Maris was surrounded by maybe fifty reporters and he’s trapped by his locker, no way to escape.

Playing with Mickey Mantle

Mickey Mantle was the best player I ever saw, the only guy who could run on his heels.

Casey Stengel was a master psychologist. I saw him do something with Mantle one day that was unbelievable. We were getting into our game uniforms and Mick had had a rough night. He was hurting pretty good, too.

He was sitting there, bent over, wrapping his legs and Casey could see us from his office window. Casey walks up to Mantle, looks down at him and says, “You’re not gonna play today” and walks away. Before Casey got back to his office, Mantle was right there and says, “Don’t you ever take me out of that lineup.”

If there was any thought that Mickey didn’t want to play that day, Casey changed it just by looking at him and saying, “You don’t want to play today.”

In meetings, Gil McDougald and I would get back in our lockers as far as we could cause we’d start laughing. Casey could talk all day long and you didn’t know what he was talking about.

One night in Cleveland we’re getting beat about 5-1 and Casey is dozing on the bench. About the sixth inning he wakes up, looks at the scoreboard, jumps up and says, “Hey, I think it’s time we got this guy.”

I think we won, 11-5 or something. He didn’t miss anything. But everybody was so professional, knew their job, it didn’t matter.

The 1960 World Series

Game 7 of the 1960 World Series, I roomed with Yogi Berra. The night before he said, “They’re gonna have Elroy Face in there tomorrow. I’m gonna hit one off him.” And he did.

During the season, when we had a good lead Casey would move Tony Kubek out to left field to replace Berra and I’d go in at shortstop.

He thought that was his best defense. I was set to do that when a ground ball hit Kubek in the throat and I had to replace him then. We really lost that game because our pitcher, Jim Coates, didn’t cover first on a routine grounder in the eighth inning.

The next spring when Coates showed up and greeted Clete Boyer, Boyer said to him, “Yeah, if you’d covered first base, we’d all be a little richer.” They never forgot it.

The worst move I made was when I retired after ’61. The Yankees wanted me to stay and they wound up playing the Giants out here in the ’62 Series.

[We were about to leave when Mrs. DeMaestri arrived home. She was asked what she remembered most about her days as a baseball wife.]

“I remember driving kids cross country.”