Comparing Eras: The Fallacy of 'All-Time' All-Star Teams

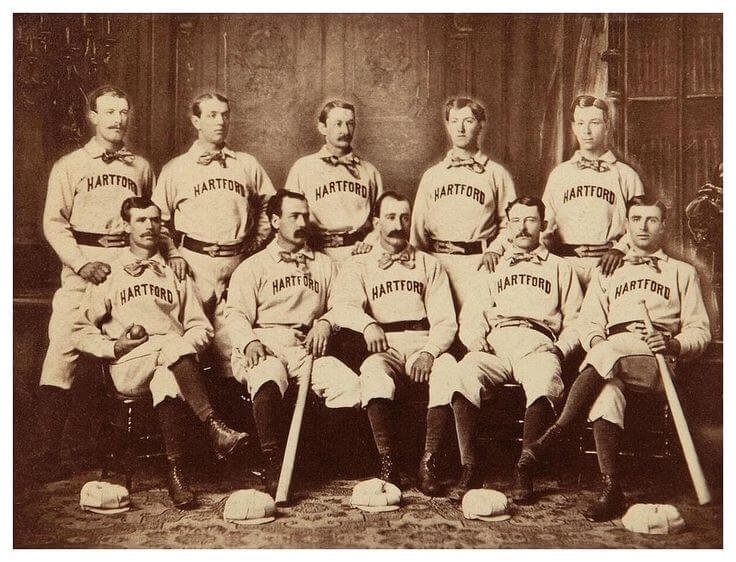

The Hartford Dark Blues, a 19th century baseball team based in Conneticuit

Compiling ‘all-time’ All-Star teams or ranking the top 100 players of all time, using convoluted algorithms and formulae, is a skewed, ultimately meaningless exercise - Norman L. Macht

Baseball from the nineteenth century through the Deadball Era has no more relevance to today’s game than WW I warfare has to today’s conflicts.

No point Comparing Eras

Sure, the objective remains the same, and the bases are still 90 feet apart, and it’s still strike three you’re out, but the changes in equipment, schedules, rules, strategy, approaches to batting, pitchers’ roles – all have made comparisons of those earlier players’ and teams’ abilities and stats with those of today misleading and useless.

The bunt – even to foil a shift – has become as outmoded as a musket.

Brushback pitches – once routine -- are now considered high crimes and misdemeanours.

Getting on base is not enough; home run hitters are richly rewarded even if they strike out four or five times for everyone they hit. Pitching by committee makes individual won-lost stats obsolete.

Connie Mack knew the Problem

Connie Mack recognized all that as far back as 1943; he’d seen them all since 1886. At his eightieth birthday celebration, he declared the practice of selecting all-time all-star teams obsolete.

Citing the many changes the game had undergone over the years, he said, “There were great ball teams in the 1880s. There were good teams in the 1890s.

Then came the beginning of this century and every ten or fifteen years there comes a new crop of great players. But when you look at all-time all-star teams no matter when they’re picked, the same three names are in the outfield – Cobb, Speaker and Ruth.

The infield never changes. That isn’t right. I think the all-star teams should be selected by the baseball writers every fifteen years.

That is fair to every player, for the game changes and new players ought not to be compared with old-timers. There are a great number of star players today who should be given proper place in all-star selection.”

What are some of the changes in the game that Mack was talking about?

Gloves

Let’s start with the glove. Well, to begin with, there weren’t any. Nineteenth-century outfielders fielded fly balls and grounders with their bare hands.

A few infielders began using thin “pancake” gloves in the early 1880s, but most disdained that “sissy stuff.”

Catchers, who stood several feet behind home plate and caught pitches on the bounce, began to move up and pitchers began throwing overhand.

A few of them put on a hand-fitted buckskin glove, sometimes reinforced with a rubber pad or thin slab of beefsteak inside.

Through the years catchers’ mitts evolved into big hard inflexible cushions which eventually became the flexible mitts of today.

As for fielders’ gloves, I can remember in the 1980s sitting in the Phillies’ dugout with my friend, 1930s shortstop Dick Bartell, putting on his old glove, then slipping my hand – glove and all – into the glove of the Phillies’ shortstop sitting next to us.

How the Ozzie Smiths of the twenty-first century would have fared with such equipment we’ll never know.

The Field of Play

Playing fields have changed from the sometimes sloping, sometimes hilly grounds of old to the manicured playing fields of today.

Creative or untrained groundskeepers created uneven results for pitchers’ mounds and base paths.

During the years the Cardinals and Browns shared Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, and the Giants and Yankees shared the Polo Grounds in New York, the fields were in almost constant use and grounds maintenance was minimal.

It was so hot in St. Louis during the summer, the infield was baked like a brick.

Changes in the Ball

Another big difference between then and now is the ball they were swinging at.

In the old “old days” the same ball was used no matter how dirty, scuffed, nicked, wet from spit or tobacco juice, or mushy it became.

How many of those do you think Mike Trout might have hit for a 450-foot home run?

(Infielders hated to play behind their spitball pitchers, knowing they’d have a hard time getting a grip on the slick ball to make a throw.)

No pitchers discarding a ball because they didn’t like it. Foul Balls and the occasional home run hit into the stands were confiscated by ushers and returned to the field.

Game Times

Which brings me to another reason you can’t compare today’s hitters and pitchers with past stars: Game times.

For more than a half-century, almost all major league games were played in the afternoon, beginning between 2:30 and 3:30 and usually ending between 5:00 and 5:30.

Because of the way the diamonds were laid out and the height of the grandstand behind home plate, home plate was soon in a shadow that gradually crept toward the pitcher’s mound, which meant that the batter was in the shade swinging at a pitch thrown out of the sunshine instead of an evenly lighted playing field.

On overcast days there were no lights to turn on or, where they were, the rules prohibited them from being used to complete a game.

Today’s sluggers might find that swinging at 100 mph pitches in the twilight dusk of a spring or autumn game might not be so productive; old timers knew that “you can’t hit what you can’t see.”

Players wearing wool uniforms – sometimes playing doubleheaders – in the July-September heat and humidity of cities like New York, Washington and St. Louis wilted; pitchers sometimes keeled over on the mound and had to be carried into the clubhouse and submerged in ice to recover.

Before lights were installed in Wrigley Field, some Cubs players blamed the strength-sapping effects of hot summers for costing them some pennants.

Today’s players enjoy private hotel rooms on the road.

No more sharing a room with another player who might snore, come in at all hours sober or not, keep you awake reading or talking – much less sharing a bed, as they did in the long-ago “good old days.”

So use whatever metrics or formulae you care to make up: Connie Mack had a point.