The Last No-Hitter in the Polo Grounds

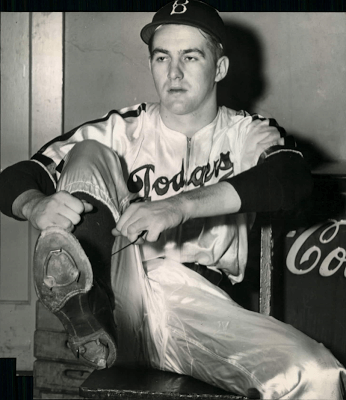

Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Rex Barney

The families of Romeo and Juliet, the clans of the Hatfields and McCoys, and the Irish Catholics and Protestants all seemed like bosom buddies compared to the tribes of New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers fans in the mid-twentieth century.

No fiercer or more antagonistic rivalry has ever existed in major league history. Separated by the East River, they were the only two teams in the same league in one city. The animosity usually infects a team’s rooters more than the competing players, but this fever was too virulent to avoid infecting the players as well.

Ebbets Field

Ebbets Field in Brooklyn was small: about 32,000 seats. The Giants played 11 games a year there, including big holiday doubleheaders. Giants shortstop Dick Bartell recalled, “We would walk around in front of the stands before a game to see how many fights we could spot. One time we were playing a doubleheader there.

Our center fielder, Joe Moore, got tickets for his brother-in-law visiting from Texas. When he returned home, the brother-in-law told the folks, “If you want to go somewhere to see some action, just go up there to see a ball game. I saw 95 fights and two games, all the same day.”

At Ebbets Field the Giants would put a cap on the end of a bat and stick it above the dugout roof, just to evoke a cascade of booing. In the Polo Grounds, as soon as a Dodger uniform appeared outside the center field clubhouse, the hostile thunder began.

Ebbets Field: former home of the Brooklyn Dodgers

Since the 1890s, no Brooklyn pitcher had ever thrown a no-hitter against the Giants, while two Giants pitchers had held Brooklyn hitless, the last in 1915. Giants fans taunted their enemies that the only way a Brooklyn pitcher would ever no-hit them would be in a night game -- with the lights out.

So it was only fitting that, ten years before their war ended when both teams departed for the gold fields of California, the last no-hitter in the Giants’ ancient Polo Grounds was thrown by a Brooklyn pitcher – in a night game.

It almost didn’t happen.

On the morning of Thursday, September 9, 1948, it was raining. It continued raining that afternoon. The Dodgers were scheduled to play the Giants at the Polo Grounds that night. Teams required their players to report to the ballpark whatever the weather as long as the game had not been called off.

Rex Barney

Second-year pitcher Rex Barney was due to pitch for the Dodgers. Every batter hated to face Barney, who threw 100-plus but was wild. In the 1947 World Series he had the Yankees scared to death. He started Game 5, gave up 2 runs in 4 2/3 innings on 3 hits and 9 walks (and 2 wild pitches).

But lately he had been in a groove; three weeks earlier he had pitched a one-hitter against the Phillies. He was ready and eager to pitch that night, even though the Giants always gave him trouble. They had a powerful lineup, having hit a record 221 home runs the year before.

Here Rex picks up the story:

At game time, 8:15, it was still raining. I sat in the clubhouse, looking out the window, fidgeting. I never could stand inactivity and I was getting nervous and tense.

When it got close to nine, the clubhouse man assured me that we wouldn’t play and brought me a hot dog. Those ballpark franks would kill a snake. I tasted that one for a week.

There were 36,000 people sitting there waiting; a Giant-Dodgers game would draw a crowd in a typhoon. The Giants secretary, Eddie Brannick, and the umpires had decided to give it an hour before calling it off.

A little after 9 o’clock Brannick climbed toward the press box to make the announcement. On the way he noticed the grounds crew removing the covers from the field. He paused, changed his mind, and turned around and went down.

The rain let up and I went out to warm up. When I finished, my catcher, Bruce Edwards, said to me, “You sure have plenty of stuff tonight.”

Every pitcher knows exactly what he has or has not given up in a game. But it’s just another game until he gets to the sixth inning and begins to think he has a shot at a no-hitter.

Leo Durocher, who until a few months ago had been the Brooklyn manager before his startling switch to the Giants, was coaching at third base, heckling me the whole time. “We’re gonna get you this inning, you no-good busher.”

When I went up to bat, catcher Walker Cooper said to me, “You’ll never last with that slop you’re throwing.”

Every time I came off the mound after an inning the fans were hollering, “You know you’re pitching a no-hitter.” The old jinx routine.

By the seventh inning you notice that all of a sudden you’re sitting alone on the bench. Nobody wants to be near you. They slide away like the Red Sea parting. Nobody speaks to you.

The Giants fans gradually began to come over to my side and I got a big ovation after every out. The score was 2-0, so the game was still on the line, and I had to remember that winning came first. But with each out I got a little more pumped up.

By the ninth, the tension had spread to the others on the field. In right field, Gene Hermanski was not a good fielder. Later he said, “I was out there praying they wouldn’t hit the ball to me.”

The ninth inning was one continuous deafening howl. It began to rain again as pinch-hitter Joe LaFata stepped in.

I half-expected him to try a bunt on the wet grass, but he struck out. Lohrke grounded out to first. And there stood my old nemesis, Whitey Lockman, between me and glory.

Bruce Edwards came out to the mound. ‘You know who this is,’ he said.

“Yes.”

He said, “What are you going to do?”

“Just throw it as hard as I can.”

I thought my first pitch was perfect, but umpire Babe Pinelli called it a ball. I yelled, “No!” Took a deep breath. Took another. Wound up and threw. Lockman lifted a high foul pop-up.

Edwards whipped off his mask and ran what seemed like two city blocks to the top of the dugout steps and caught it. I leaped about two feet in the air and Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese were the first to reach me.

And then we were running out to the clubhouse and here was Durocher, who had been my manager until two months ago and my heckler that night, running alongside me. ”I’m proud of you kid,” he said and ran on past me.

The next day at the Polo Grounds when I started down those twenty or thirty steps from the clubhouse door to the field, instead of the usual names and jeers and boos, I heard nothing but cheering.

Ten years later there was nothing but the sound of the wind and the pigeons in the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field.