The Flycatchers

Joltin Joe DiMaggio knew how to grab ‘em

The much-ballyhooed and often replayed catch made by the New York Giants’ Willie Mays in the 1954 World Series is the best example of how a play seen by millions on TV and reshown over and over gains more provenance as ‘The Catch’ than more spectacular plays made in regular season games or in pre-TV years.

National League players said of the Polo Grounds that it was a taxi ride from home plate to center Field – 483 feet.

You could run all day before you ran into a barrier. Willie Mays later downplayed the catch, recalling many more difficult plays he had made.

Willie Mays’ iconic catch: 1954 World Series

Spectacular catches, many little known nor long remembered, have been made throughout baseball’s lifetime. Some occurred in pre-TV World Series; you have to read about them to know they happened.

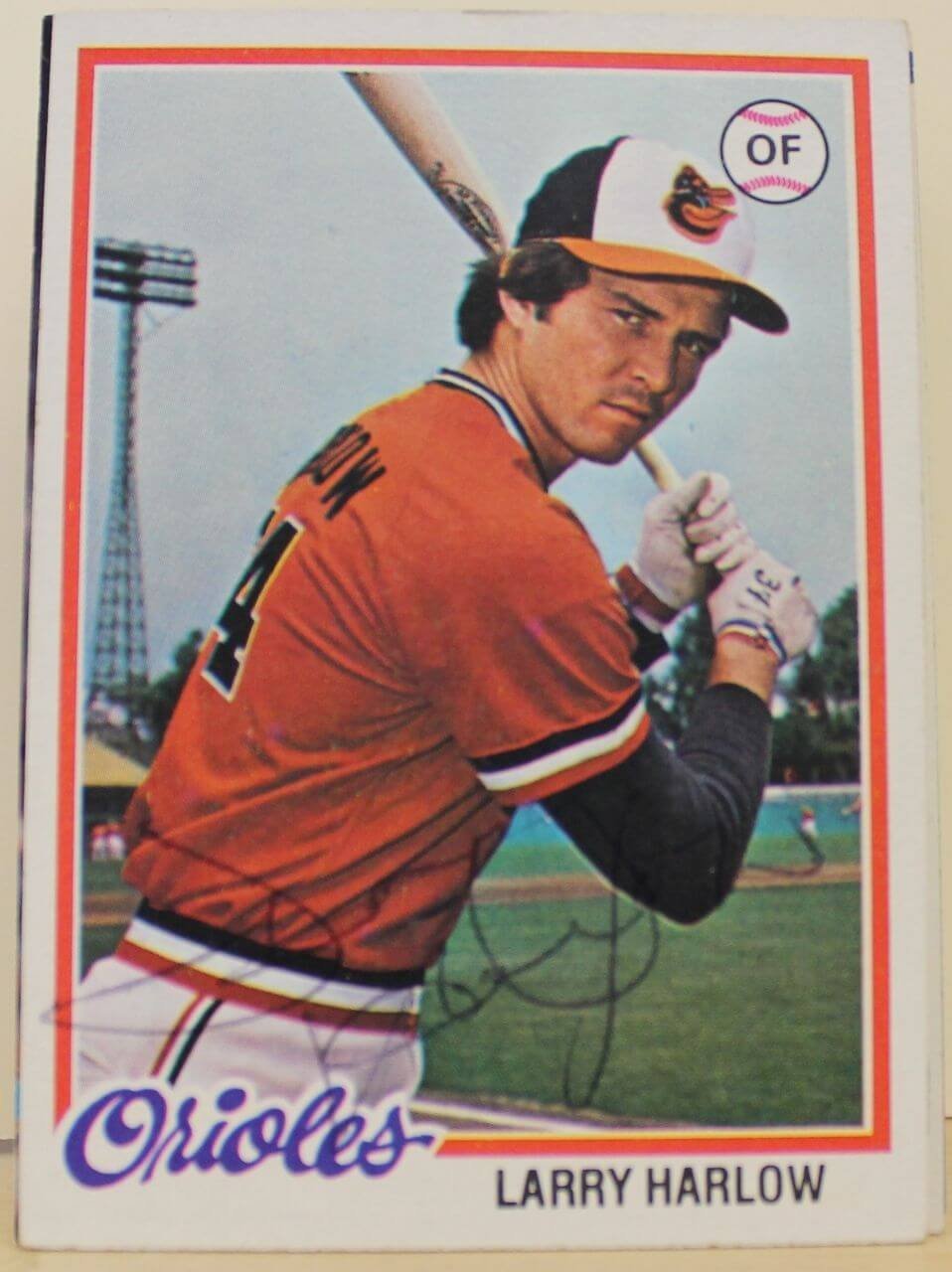

Larry Harlow

Unless you were an Orioles or Angels fan a half-century ago, you probably never heard of Larry Harlow. A 6’2” left-handed outfielder, Harlow played only one full season during his four years with the Orioles.

But he made one memorable catch, witnessed by only a handful of fans who called it the greatest they had ever seen at the old Memorial Stadium where the Orioles played until Camden Yards opened in 1992.

It was a night game against Detroit that drew about 5,000 fans in May 1978. Harlow was playing center field. John Wockenfuss, a right-handed hitter, was up. Harlow is shaded a little toward right center. The ball is hit to left center.

Larry Harlow

Harlow took off flying, leaped above the bullpen fence and hung there, the post in the middle of his back, and caught the ball on the other side of the fence.

Teetering on top of the fence, he saw the bullpen coach waiting to catch him, but the left fielder pulled him back onto the field, scraping his ribs on the way down.

The game was televised, and maybe the catch made the TV highlights that night, but then it was forgotten, except by those who saw it.

DiMaggio, Blair and Ashburn

The Yankees’ Joe DiMaggio, the Orioles’ Paul Blair and the Phillies’ Richie Ashburn are a few who rarely made memorable catches. That’s because they made them look easy. Blair and Ashburn played as shallow center field as anybody ever did.

They were fast and, like DiMaggio, always got a jump on the ball. They made it impossible for anybody in the ballpark to see the ball hit the bat, then see them take their first step in pursuit.

Fans – and I was one of them -- never saw DiMaggio make a diving or sliding catch. Or break the wrong way, then double back, turning a routine catch into a spectacular one. But we saw him weave his way gracefully through the maze of monuments that stood in the outfield at Yankee Stadium to make a catch.

Al Gionfriddo

That kind of fly-catching efficiency doesn’t make the TV highlights, like another often-shown World Series “mistake” does. In Game 6 in 1947, Brooklyn Dodgers’ part-time outfielder Al Gionfriddo made a catch off DiMaggio with two men on. Gionfriddo, a lefthander, had entered the game in left field in the sixth. DiMaggio hit a blast headed for the bullpen.

Gionfriddo is seen racing toward his right, reaching out his gloved right hand and spearing the ball just before it crosses the low bullpen fence. If the glove had been on his left hand he would have missed it.

But, more important, if he hadn’t broken a few steps the wrong way when the ball was hit, it would have been a routine catch.

Instead it’s immortalized because a) it was a World Series catch, and b) It’s still shown, not as an example of Gionfriddo’s fielding ability, but as a rare example of DiMaggio’s showing any emotion on the field as he kicked the dirt while approaching second base after the catch.

Long before there was instant replay or TV or radio, before anyone reading this was alive, even before fielders wore gloves, there were catches being made that thrilled those watching the action, but were otherwise soon forgotten. Occasionally they occurred in a World Series or other noteworthy circumstances, and have been preserved by baseball historians.

Al Simmons

One of the great catches of the 20th century is all the more notable because of the future Hall of Famer who hit it as well as the future HoF who caught it.

The two mightiest powerhouses of the time – the Yankees and the Philadelphia Athletics, had each won three of the last six American League pennants: the Yankees in 1926-28 and the A’s 1929-31. When they met at Shibe Park in Philadelphia on June 3, 1932, hits rained through the air like the bombardment of Ft. McHenry.

After 2 hours 55 minutes, 14 walks and 36 hits including 9 home runs and 5 triples, the final score was New York 20, Philadelphia 13. A crowd of about 5,000 witnessed the 2 hour 55 minute siege.

Among the heavy hitters, Lou Gehrig became the first American Leaguer to hit 4 home runs in a game. In the ninth inning, he almost became the first (and last) to hit 5.

The A’s left fielder Al Simmons had been moved to center field in the top of the ninth. Eddie Rommel became the fifth pitcher for the A’s. With one out and the bases loaded, Gehrig came up to bat.

A rookie catcher for the A’s, Ed Madjeskie, recalled, “All the A’s on the bench wanted to see Gehrig hit number five. They wanted Rommel to groove one for him.”

Rommel was a knuckleball pitcher. Even if he grooved one, Gehrig would have to supply all the power to drive one into the seats.

Shibe Park was a city-block rectangle with home plate at one corner and a center field flag pole in the opposite corner, a distance variously measured between 486 and 515 feet. Center field was a vast pasture to patrol.

Gehrig hit a drive headed for the flagpole. Everybody was running, including Simmons, who reached the flag pole and made a one-handed catch with his back to the infield. The New York Sun commented that any other gardener but Simmons might have seen Gehrig’s final attempt buzz over his head. . .”

Simmons called it the greatest catch of his career. The catch also denied Gehrig the one-game total bases record.

Sam Rice

If there were a category of Great Tries, perhaps this controversial “great catch” might belong there. You be the judge.

The scene was Washington’s Griffith Stadium, the event Game 3 of the 1925 World Series between the Washington Senators and Pittsburgh Pirates.

Griffith Stadium occupied a city block, but it was far from square. Down the left field line, the fence was 424 feet from home plate; it was only 326 down the right field line. Seating capacity was only about 30,000.

To accommodate the demand for World Series tickets, temporary seats were installed in front of the right field stands, with a four-foot-high fence in front of them. The crowd included President Coolidge and his wife, Grace (a lifelong Red Sox fan).

After the first two games in Pittsburgh were split, Game 3 took place in Washington on a cold, windy Saturday, October 3. Washington led, 4-3, in the top of the eighth. Sam Rice, a converted pitcher who had started the game in center field, moved to right as Earl McNeely replaced him in center.

With two out, Pirates catcher Earl Smith, hit a fly ball to right, headed for the temporary seats behind the fence.

Sam Rice’s controversial catch: World Series 1925. Image credits: Flickr

Rice raced toward the spot, leaped at the fence, made a backhanded catch, tumbled over the fence and disappeared among the spectators. There was no sign of him, no uplifted glove with the ball in it – for how long? Various newspaper accounts timed it from ten seconds to a minute.

There were no outfield umpires in those days. It was second base ump Cy Rigler’s responsibility to race toward the bleachers and make the call. When Rice reappeared holding the ball, Rigler signaled “Out.”

Pirates manager Bill McKechnie came out hollering. The four umpires conferred and backed up Rigler’s call that Rice had held the ball long enough, even if he then dropped it. (How Rigler could have known that if he didn’t see it was not explained.)

McKechnie stormed over to where Commissioner Landis was seated behind home plate and said that if the Pirates lost the game (they did), he would protest. Landis told him that disagreeing with an umpire’s call was not grounds for a protest.

Pittsburgh papers reported that at least three Pirates fans had been in the bleachers and witnessed the “catch.” They were prepared to sign affidavits that Rice had dropped the ball and a small boy had picked it up and handed it to him.

As for Rice, he was quoted as saying he was “stunned” and that was what took him so long to reappear. He also supposedly said – and repeated over the years when asked about the catch, “The umpire said I caught it.”