Two Managers: Sparky Anderson and Billy Martin

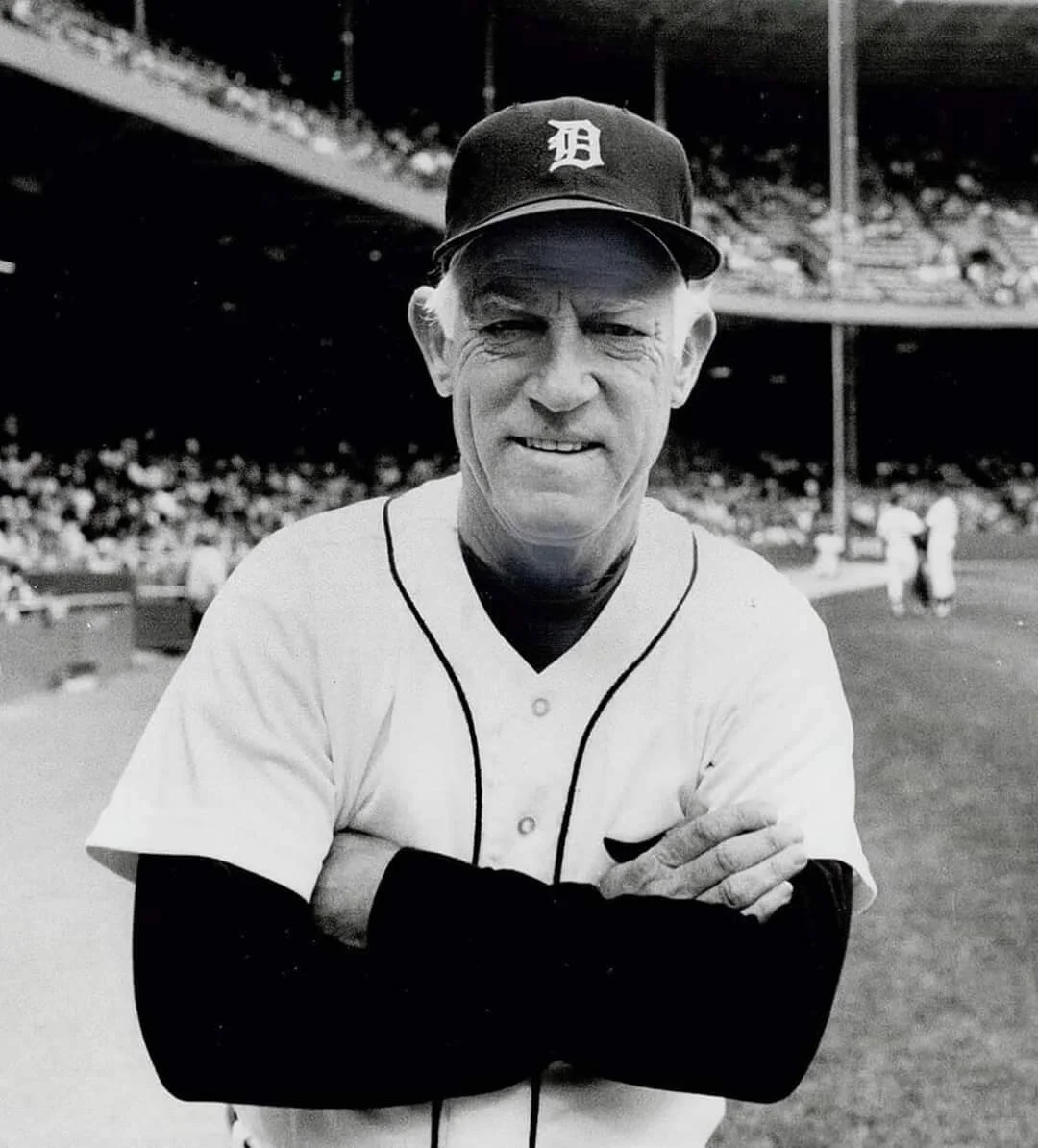

Sparky Anderson: wherever he went, he won! Image credits: Pinterest

Ever since the National League began 150 years ago and the American 25 years later, club owners have dealt with the problem of choosing managers who could win championships for them.

The fact that the two most successful managers of the first third of the twentieth century, John McGraw and Connie Mack, were so unalike in methods and temperaments and dealing with players left club officials with no template to follow.

Of the hundreds of managers who have been hired and fired over the years, no prototype has yet emerged for hiring a winning manager. That may be because in the end it's the players who win or lose, not the managers, regardless of their leadership qualities.

To explore the relation or lack of same between managers' qualities and their teams' records, let's look at two examples whose managerial careers overlapped in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Sparky Anderson

George “Sparky” Anderson was a light-hitting second baseman who played one year in the major leagues with the 1959 Phillies. It was not a pleasant experience. The Phillies were in one of their cellar-dwelling spells. He found the players' attitude, as well as that of the manager and coaches, lackadaisical. They had finished last in 1958 and seemed resigned to the same fate in '59. (They would lose 99 games.) Practices and workouts during the season were sporadic and disorganized.

Anderson batted only .218, but he was a fiery, hustling player to whom winning was everything. His attitude was if you didn't play to win, there was no point in playing at all.

When he became a manager in the minor leagues, he was so driven to win, whenever his team lost a game, there was an extra practice session the next day. He had a hot temper that took several years to get under control. But from the beginning he took an interest in his players and their welfare. His door was always open to them for their concerns or complaints. And wherever he went, he won.

Meanwhile, in Cincinnati, the Reds' astute general manager, Bob Howsam, was building what would become the Big Red Machine. And when it was ready, in 1970 he chose 35-year-old Sparky Anderson to drive it. Sparky brought his intensity to his first big league spring training camp, which some players described as a “slave camp.”

Just as he had in the minor leagues, he entertained players' complaints but never put any individual's gripes ahead of the team. He could be tough when he had to be, in one case setting a hot-headed starting pitcher straight for complaining about being relieved early in a game, to avert his spreading discontent. (Sparky was labeled “Captain Hook” for his tendency to change pitchers early and often.)

“I am the manager and they are the players. That's what they've got to realize. Whatever I do is for them. The better they are, the better I am. That's what I've got to realize. . . My job is to try to keep those twenty-five guys in the game at all times and that's all. I believe they have problems like you and I do, and I try to find out what they are. You've got to understand what they're thinking and where they're coming from.”

In his case that applied even to the clubhouse employees, whom he knew by name and took to lunch once a year.

In his first year he took the Reds to the World Series but lost to the Orioles. They made it to the Series again in '72 but lost to Oakland. In '73 they lost the NLCS to the Mets. In '75 and '76 they were World Series champions, in 7 games over the Red Sox and a sweep of the Yankees.

The Reds finished second in each of the next two years. When Bob Howsam retired after the 1978 season, Reds' owner Marge Schott, who knew nothing about baseball or people or public relations, fired the popular Sparky. Several teams were eager to sign him. The Detroit Tigers won.

Although he led them to only one World Series title, Sparky managed the Tigers for the next 17 years. He never changed his open-door policy with his players, often circulating in the clubhouse to read their moods or just visit with them.

While some managers chafed at the demands on their time made by the press, he understood that they had a job to do and encouraged his players to cooperate with them. He always arrived at the ballpark in the early afternoon for night games, his office open to players, press, broadcasters, old baseball friends.

In the early 1990s, some younger managers were succumbing to the pressure of the job, complaining of being “burned out.” One afternoon in the visiting manager's office in Baltimore, Anderson reflected on his life in baseball.

“I live a life I never imagined. I go first class, best hotels and food, make a lot of money, go home to California every winter and paint my house, play with my grandkids and play golf and then, isn't it terrible, I have to leave all that and go back to Florida for spring training. Isn't that a tough life?”

But time, as it does to all, caught up with him. He retired after the lockout-shortened season in 1995, was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2000 and died from the effects of increasing dementia in 2010.

Billy Martin

Billy Martin had a mouth with no brakes or guardrails, a penchant for fist fights which he seldom won, and a taste for alcohol he could not control. His favorite tactic was what was called in baseball lingo a hundred years ago “Copping a Sunday” – getting in the first punch when the other guy wasn't looking for it.

As a young scrappy, aggressive second baseman, he was a light hitter, but he wanted the bat or ball in his hands when the game was on the line. It was that attitude that impressed Casey Stengel when Stengel managed the Oakland Oaks to the Pacific Coast League pennant in 1949 with the rookie second baseman in the lineup. “He never let me down in the clutch,” Stengel said. When Stengel was signed to manage the Yankees in 1950, he insisted they buy Martin from the Oaks.

Martin brought with him a chip on his shoulder as big as a 2x4. Though he stood almost six feet tall, he was skinny, never weighing more than 165. If an aggressive base runner slid into him or a pitcher sent him sprawling with a brush-back, it fired him up like tinder.

If he couldn't chase down the enemy under the stands after the game, he sometimes stalked him until he found him the next day. He fought with teammates and fans when he was drunk. Later, as a manager, he fought with his own players, once suffering a broken arm in a parking lot fight with Yankees pitcher Ed Whitson, who outweighed him by 30 pounds.

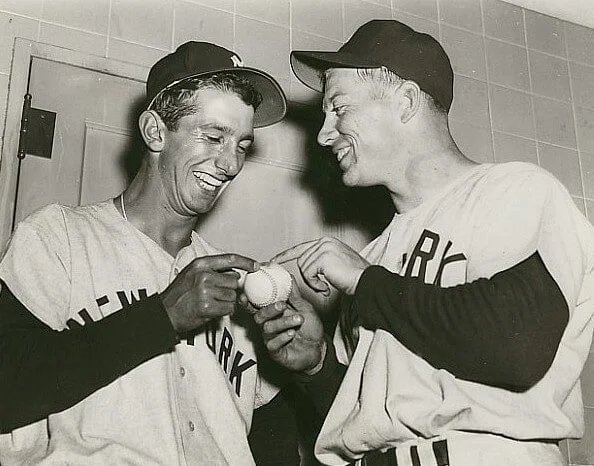

Billy Martin became good friends with Mickey Mantle, but the Yankees could only tolerate so much from the hot-headed manager. Image credits: Pinterest

But he produced up to Stengel's expectations. The Yankees proceeded to win five straight pennants and World Series. Martin was a career .250 hitter, but he hit .333 in those Series, including batting .500 with a record 23 total bases in '53. Those teams also had a corps of stars, headed by Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford, who lit up the Broadway night life circuit. Martin became a member of the clique, which was tolerated by management until they were involved in a wild brawl in a night club that made headlines.

In 1957 the Yankees had enough of Billy Martin and traded him to Kansas City. It is telling that he played for five different teams in the next five years.

Sam Mele was a 10-year outfielder who was named manager of the Minneapolis Twins in 1961. He was an easy-going leader of a talented team that finished second and third in the next two years, then slipped to sixth in 1964. Mele figured he needed somebody to light a fire under them. He hired Billy Martin and veteran outfielder Jim Lemon as coaches to drill them on fundamentals in daily practice sessions

Sam Mele

“Martin and Lemon drove those players hard. If they had a guy practice something 99 times and he complained, they'd tell him he'd have to do it another hundred times until he got it right.”

The Twins won the pennant but lost the seven-game World Series to Los Angeles. A few years later they fell to sixth and Mele was fired in 1968. Twins owner Calvin Griffith wanted more fiery leadership and chose Billy Martin to provide it in 1969.

As a manager, Martin was as warm and caring as a slave driver. He showed up at the ballpark near game time and rarely went into the clubhouse. Like most managers who had not been a catcher or pitcher, he knew nothing about pitching. But that didn't stop him from berating his pitchers in the dugout during a game or in the press.

Catcher Johnny Roseboro had been traded from the Dodgers to the Twins. He was used to the quiet but tough leadership of LA manager Walter Alston and was shocked by Martin's behavior.

Johnny Roseboro

“Martin was volatile and unpredictable. He had the Leo Durocher fire to win, but he wasn't very good at handling players. He was angry a lot, jumped on your case a lot, got on the pitchers.”

But they won their division before losing to the Orioles in the ALCS. And a pattern began that would last for the rest of his life. Despite his teams' records – they were usually in the top three in the standings and led the Yankees to two World Series, which they split, he was fired eight times (including three different times by the Yankees) in 16 years.

It wasn't his fists or his drinking, but his mouth. He didn't hesitate to sass his employers, publicly criticized them as well as his players, front office personnel, league officials, right up to the commissioner.

Yet he always found another job because he brought excitement and fans to the ballpark and his teams played winning baseball.

Billy Martin managed his last game on June 22, 1988. He died on Christmas Day 1989 when he and a friend had been drinking and his pickup truck, driven by his buddy, skidded on an icy country road and fell 300 feet down an embankment.

Conclusion

So who was the better manager in your opinion? If you owned a team, which would you hire? Would you base your decision on the number of World Series appearances? Or would a better criterion be their career won/lost records? That might not be helpful: despite their different managing styles, Anderson's was .544; Martin's was .553.