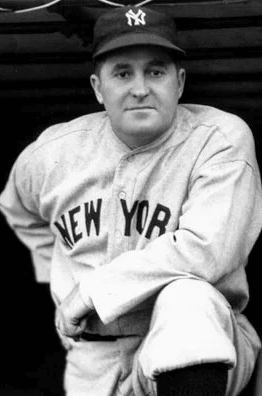

The Meteor-Like Rise and Fall of Hack Wilson

Image credits: The 3-0 Take Facebook

No other American sport has had as many odd characters as baseball. That's partly because so many thousands of players have appeared in at least one major league game over the past 150 years, and partly because, unlike other sports, there are no so-called normal or stereotypical sizes, shapes and weights for baseball players as there are for football and basketball players and jockeys.

That's why you'll see 5-foot-4 outfielder Wee Willie Keeler just down the wall from 6-10 pitcher Randy Johnson and 150-pound shortstop Phil Rizzuto along with 230-pound catcher Ernie Lombardi in the Hall of Fame.

There have been a one-armed outfielder, one-handed and one-legged pitchers, deaf players, stars and scrubs from all backgrounds and levels of education.

Perhaps the most unlikely player of all to wind up on the walls of the Hall was Lewis “Hack” Wilson, whose career lit up the baseball world like Fourth of July fireworks for five years, then as quickly fizzled out.

Wilson was born an alcoholic, inheriting the condition and its physical and mental manifestations from both his parents. He was built like a miniature caricature of a wrestler: 5-foot-6 with a large head, an 18-inch neck and a barrel chest, but small hands and feet. As a teenager he did heavy manual labor and developed huge biceps that enabled him to drive a baseball hard and long.

He began as a catcher, but a leg injury caused him to switch, implausibly, to center field, where he was neither swift nor sure-handed. When he tore up Class D pitching, hitting .364 and 35 home runs, the New York Giants bought him in 1924.

Injuries hampered him, but he hit some long home runs for the Giants and played in all seven games of the 1924 World Series loss to Washington. But he was not John McGraw's kind of player, drawn too much to the nightlife of New York, and the Giants sent him down to Toledo in 1925.

Jo McCarthy

They could not have done him a bigger favor. The Cubs drafted him in the Rule 5 draft and Hack landed under the care of the best manager he could have played for – Joe McCarthy. McCarthy did not believe in fines, bed checks, detectives trailing his players.

He understood Hack had a drinking problem and a short temper, neither of which he could control. But he always showed up at game time and produced. So McCarthy bailed him out of jail after drunken brawls, speakeasy raids, fights with teammates and opposing players, and occasional assaults on heckling fans.

Baseball's offbeat characters have always been fodder for imaginative typewriter jockeys of the press box. Given Joe McCarthy's patience and kindly approach to Wilson's problems, this yarn may have a semblance of truth – or at least possibility – about it.

Hack Wilson had his problems - but he showed up for Joe McCarthy. Image credits: CND Bleacher Report

The story goes that one day McCarthy called Hack into his office. On his desk he had a worm and two glasses, one with water in it and one with gin, He said, “Watch this, Hack.” He put the worm in the glass of water. It swam around having a good time. Then he took it out and put it in the gin. It flipped and twitched and fell to the bottom of the glass, dead.

“Now Hack,” he said. “What does that teach you?”

Hack said, “If you drink, you won't have worms.”

Wilson repaid Joe McCarthy's patience and kindness with the most productive five years any hitter ever produced. From 1926 through 1930 he led the NL in home runs four times and RBIs twice. He averaged 183 hits, 35 home runs and 142 runs batted in. In 1930 he set an NL record of 56 home runs that lasted for decades and a record 191 runs batted in that still stands.

In the 1929 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, Wilson batted .471, but that was overshadowed by his losing two fly balls in the sun in the seventh inning of Game 4 as the A's, losing 8-0, scored 10 runs and went on to win the Series.

Rogers Hornsby

And then it all ended. Joe McCarthy was fired by the Cubs' owner, Phil Wrigley and replaced by Rogers Hornsby, as different from McCarthy as you could find. He was cold, impersonal, full of rules, tough on curfews and discipline, quick to impose fines.

Wilson wasn't hitting, was benched and eventually limited to pinch-hitting. His production fell to .261 and 13 home runs. Though still a fan favorite, his time with the Cubs was over and with it, his glory days.

End of the Line

The Cubs traded him to the Cardinals, and when he wouldn't agree to a three-fourths pay cut, the Cardinals sent him to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Though he had a decent season, hitting .295 with 23 home runs and 123 runs batted in, his drinking intensified and his weight ballooned to 230 pounds. His range and mobility in the outfield declined rapidly.

There is one more incident in the life and times of Hack Wilson that players of the time remember. It occurred at Baker Bowl in Philadelphia. Baker Bowl, named for prior Phillies' owner William Baker, was an old, rundown, odd-shaped ballpark. It resembled a shoe box, with the left field wall at the toes end of the box, 341 feet from home plate, and the heel end at the first base line, which put the right field fence a mere 280 feet from home plate.

The right field fence was made of tin that rang with a clang when line drives banged off it, as they often did. Right-handed batters aimed for it as well as lefties.

On July 4, 1934, the Dodgers were at Baker Bowl for the holiday doubleheader. Wilson started the second game in right field. The Brooklyn pitcher was right-hander Walter Beck. In the bottom of the first inning, Beck had nothing. He gave up three singles, walked three and threw two wild pitches.

After the third walk, Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel had enough. But he stayed in the Dodgers dugout and waved for his catcher, Al Lopez, to go out to the mound while a relief pitcher trotted in.

While all this was going on, Hack Wilson lay down in the outfield grass near the tin fence. The frustrated Beck, sore at himself, at Stengel and the world in general, turned and saw Hack snoozing on the grass. He fired the ball against the right field fence. It hit like a cannonball. When Wilson heard the bang, he jumped up, raced after the ball and threw a strike to second base. (Thereafter, Beck was known as Boom Boom Beck.)

The Dodgers released Wilson in August. He signed with the Phillies, who released him three weeks later. His last hit was as a pinch-hitter in his last time at bat. He finished with a .307 career average.

Wilson died in 1948 at the age of 48. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1979.